At my mom’s 80th birthday, I ended up sitting next to my Dad’s old lawyer, let’s call him Uncle Kasra, an Indian-Canadian man of Farsi background with a beautiful wife and two dynamic daughters, who we saw from time to time when we were growing up. Kasra has a rich voice, slightly foreign. It’s not that there’s an accent, it’s that there’s a melody to it, charming and engaging that was unlike other Canadian voices that I knew.

He told a funny story. A woman had owned a dress shop in my father’s building, below his offices. It had flooded. Dad and his business partner, who we treated as family, and know as Uncle George, sat face to face with Kasra. ‘How much damage was there?’. But they wouldn’t say. Or rather danced around the truth. Finally, he forced it out of them. It had caused considerable damage. She sued them.

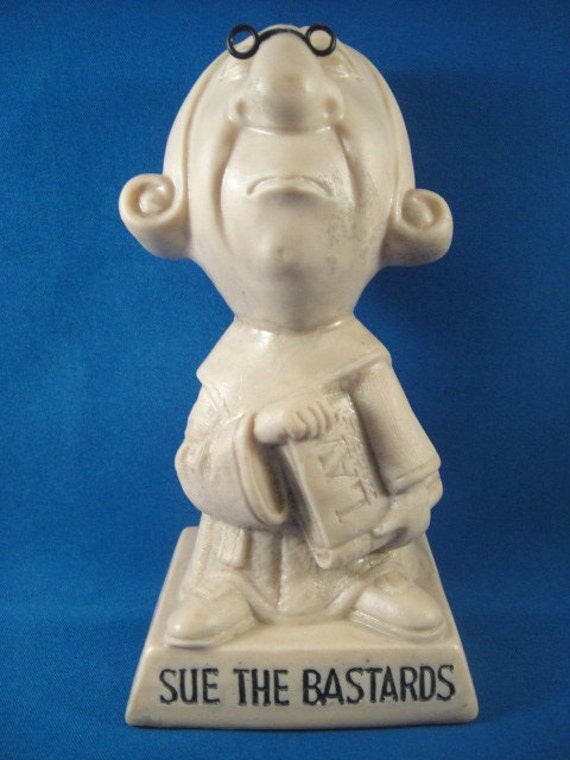

There seems to have been no discussion of an assessment of damage and offering to fairly pay for it. Business for Dad was a game. It was a game to figure out how to pay less taxes, a game to find out if there were ways to beat the system. His favourite phrase, written at the base of a small statue of a bespectacled man with lawyerly hair curls, was “Sue the Bastards”.

In the court proceedings, the woman apparently decided to cosy up to Kasra. She thought she could ‘wiggle-waggle’ her way into a better position. But why would Kasra ever betray his clients for a bit of that? He played along, and gave her information. She fired her lawyer! Why would she do that? She obviously thought that she had an inside track with Kasra and would come out on top. The case continued. Kasra delayed the proceedings as much as possible.

After two years, he was pleased to inform her: the time limit for her claim was no longer valid.

Could she call her old lawyer?

Of course.

She called the lawyer that she had fired nearly two years before. He informed her: after two years, her claim was no longer valid.

If she had kept her lawyer and not tried to get more and more funds, she would have received five, maybe seven thousand dollars. Instead, she got nothing.

Completely true, Kasra told me.

It’s a lovely fable. Portraying my father and his business partner as slightly mischievous children. A wanton woman failing in her attempts to use feminine guiles in the service of greed. The authority of law. The collusion of men. The friendship of men.

Kasra told me two other anecdotes. One, that Dad used to pack bottles of alcohol into his briefcase and bring it out at business lunches, is a terrifc image but doesn’t have enough detail to spin out further.

But the anecdote was about how they met.

He was introduced to my father in 1967 while working at a law firm. The other lawyers warned him: this one doesn’t pay his bills. Get a deposit up front.

That’s what Kasra then requested of my father, who then raised hell with Kasra’s boss, who managed to placate both sides and say, let’s do this as an act of faith among all of us.

But what Kasra discovered was something else: it was not that my father did not pay his bills, it was that he would only pay his bills if happy.

And with Kasra, happy he was. After Kasra sent an invoice to Dad, he received a phone call, father’s infamous low gruff voice barking at him. ‘It’s about your invoice,’ he said.

What had he done? Kasra was frightened, this intimidating man who had a bad reputation with the other lawyers.

‘You’re charging too little,’ my father told him. ‘I won’t pay until you charge more.’

‘He made me,’ Kasra told me.

Since Dad was always suing someone or being sued, he brought lots of business to Kasra. But more, whenever a client would come into my father’s notary business, or to do a real estate deal, Dad would say, ‘You have McGillicuddy as a lawyer? Why would you do that? I have the best lawyer in town. Kasra is who you need to see.’

The only coda that I’ll add to this tale is that in my teenage years and into my young adulthood, I suddenly discovered the many prejudices the world had against South Asians. In Vancouver, racism against the Sikh community was strong. In other locations, there were broad brushstrokes drawn about various Indian immigrants as poor or untrustworthy.

It was always a strange shock to me through most of my life, this racism. I realise in retrospect that I was surprised not just by the plain stupidity of pit, it was that through Uncle Kasra and his family, I’d actually gotten an opposite stereotype. I grew up believing thought that all Indians would be as sophisticated, charming and intelligent as Uncle Kasra, recounter of stories, friend of my father.