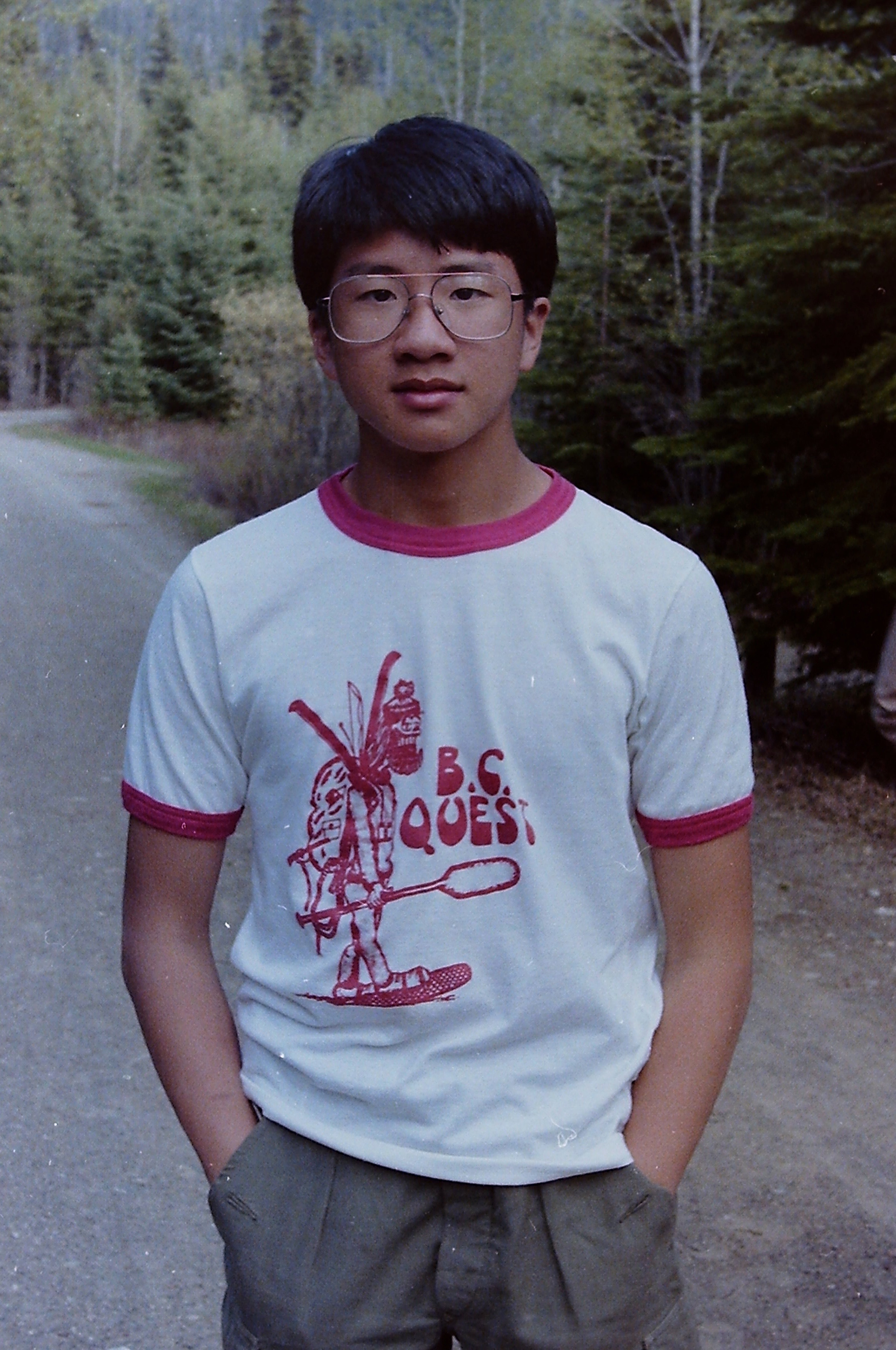

When I was fifteen years old, I entered a program at my high school in Vancouver called B.C. Quest. It was touted as an outdoors education program, and become infamous in 2006 when one of our teachers was involved in a high profile court case because of having relationships with students at the time. Years before #Metoo arrived, one of those students, as an adult, had realised that it wasn’t quite right, what she’d been through, the power differential in their ages, that he groomed multiple young women and would perform oral sex on them so they would, I think this was his reasoning, be ready and experienced for future boyfriends.

This year, I’ve been watching TV shows about cults. First there was Wild, Wild Country on Netflix, the amazing story of the period when Osho set up camp in Oregon, with his right-hand woman, Sheela, and their shenanigans. And then because I’d told a friend how much I liked it, he recommended How I Created a Cult, the story of Andrew Cohen, an American guru, and his followers.

I’m only partway through it but it’s brought back lots of disturbing memories of how the three male teachers of B.C. Quest purposefully created a cult-like atmosphere. The reason why a cult works is because it offers something positive to its followers. Many of us gained a great deal from being part of the program. For me, never being physically active or gifted, I learned that I could hike, canoe, cross-country ski and kayak.

I was introduced to the beautiful great outdoors in one of the most beautiful parts of the world. Because we were out of the classroom for the one semester of the program, and spent all our time with other 60 or so students, I formed much deeper friendships than I had before. Occasionally, the teachers would recognise me, and praise me in front of the others, which had not happened before: they detected my writing ability and intelligence, but more so, a willingness to be open, emotional and vulnerable.

And yet, two years later, when I left high school on scholarship to go to an international school, I would tell my new classmates about this amazing program that I did that I learned so much from because they were always playing tricks on us, and forcing us to grow up and learn from our various bad behaviour. Yes, there were always ‘lessons’ that we learned, to be better people, because we were irresponsible, lacked respect or were immature.

And I remember, when telling new friends about this, that not one of my classmates was even open to hearing much before they would indicate, to a person, that it just didn’t sound right.

And it wasn’t. For the five months or so of the program, they’d created an atmosphere where we were all to jostle for their attention and compete to be the most worthy, whether in physical prowess or commitment to the environment. A group identity was encouraged where outsiders were scorned. We were constantly being punished as a group so that we would learn to be better people: did we not clean our camping equipment properly, complain too much?

I have the memory of one of our classmates, insolent obviously, being made to sit in a tub of water, on a podium at the front of the large open-tiered space that we hung out in. The good thing is that he took it in stride, and given a paddle, started to pretend to be canoeing. But I knew at the time how wrong it was: the public humiliation by teachers of a student in front of his fellow students. And why? So we would step into line.

Because they were so effective at what they did, we stuck together long after the program ended, and a significant number of us then went on to pay for being part of group expeditions. The summer after the program finished, I went to the Queen Charlotte Islands, with the abuser described at the top. It was unbelievably beautiful: the ocean, the wildlife, the bald eagles, and abandoned totem poles. As was the pattern of the trips, we were all encouraged to sunbathe nude, which he believed was a way of getting us comfortable with our bodies and to work against the prudishness of Canadian society. Of course, we did what was expected, and it was fine, albeit a bit strange, and not really creepy or abusive, I think.

There was one incident of a silly mind game with the whole group, but it wasn’t terrible. We had just enough food to last us until the end, but some of us had noticed that Tom had been eating ‘our’ food, and so it didn’t look like there would be enough food left for us. I think it was just to sow dissent and see what we would do. I remember one tripmate being really worried about it, and me snapping at him to just let it be. It would work out, and I didn’t want to raise a fuss. And that’s how it turned out, as Tom and his crew cooked us dinner on the last night, so we didn’t have to worry about our food supply. Such silly mind games… but in such a gorgeous setting.

The summer after that, I went on a two-week canoeing trip from Whitehorse to Dawson City. How amazing it was to see the Yukon, such stark beauty, and such a contrast to the suffering I felt where I was bullied, daily, by the teacher’s “assistant”, someone a year or two older than we were, a high school dropout, who was jealous of the scholarship that I’d found out about a month or two before.

The rest of the people on the trip, except for one, treated me as toxic, having fallen into line with the cult of bad behaviour. Afterwards, I couldn’t believe that I’d actually paid to be on a trip where I’d been bullied and purposely made to feel like I had little worth.

In any case, I escaped that cult and most others did as well. We got on with our lives. A few years after I left, one of the students kept notes for the whole semester on all of the teachers’ bad behaviour, and this was used to fire them, shut down the program and replace it with something else. I’m pretty amazed to know that Trek still continues to this day. The daughters of one of my friends from B.C. Quest are doing the program right now! After the scandal and court case broke out, there was a TV documentary, School of Secrets, where a number of people I knew from the program were filmed, sitting around a campfire, reflecting on the situation and the past: our strange, own, private high school cult experience.

Well put. It was an intense time. Until recently, i found my primary reflection, applied excusingly, was that they got our attention and focussed it on some worthy and interesting things. At that time in my life, no adult had that kind of influence. I mostly landed on the “right” side of the teachers and escaped the majority of abuse. But I was really moved when at our 30th high school reunion, a fellow Questie expressed regret that he never stood up for me against the nick name I was given: Sloth. He’d held that for 30 years, and we werent even close friends. I remembering defending the validity of the name, even years later, arguing with my best friend who thought it wasn’t accurate. Say no more, abuse is insidious.

Agh. A mean nickname. I didn’t remember that. I think one of my last straws was that even though I had started to question what had happened, I still wrote, early at my time at Pearson College, a letter to the ‘boys’, expressing my gratitude at changing my life. I found out later that of course they had read the letter out to the whole class of new Questies, a lesson for them that they too, could, fall under the influence of Tom, Dean and Stan because the boys were so amazing and deserving of such idolatry. I remember feeling a little bit queasy, learning of this, and yet it was so clear too: our growth, us being exposed to worthy and interesting things, they were lucky by-products of a program that was mainly to fuel their own egos, pay their bills, get girlfriends and play mind games on us. As you said… insidious.